Eat For Understanding: Service Design

The Problem

Minnesota is home to the largest population of Somali immigrants in the country, but our local health infrastructure did not meet the needs of our community, specifically when addressing mental health. Due to stressors of relocation and trauma from the 1991 civil war, there is a high prevalence of PTSD, depression and generalized anxiety disorder in the Minnesota Somali population. According to a multi-year study of Somali refugees at a Minneapolis Clinic, 64% of their Somali patients over the age of 30 suffer from PTSD & depression.

Hennepin Healthcare, one of Minnesota’s Level I Trauma Centers, identified mental health as a primary initiative through its Community Health Needs Assessment. Funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, my team was brought on to identify and address barriers to mental health through community engagement and partnerships.

How might we understand Somali community perceptions of mental wellbeing, and create community- identified solutions?

The Solution

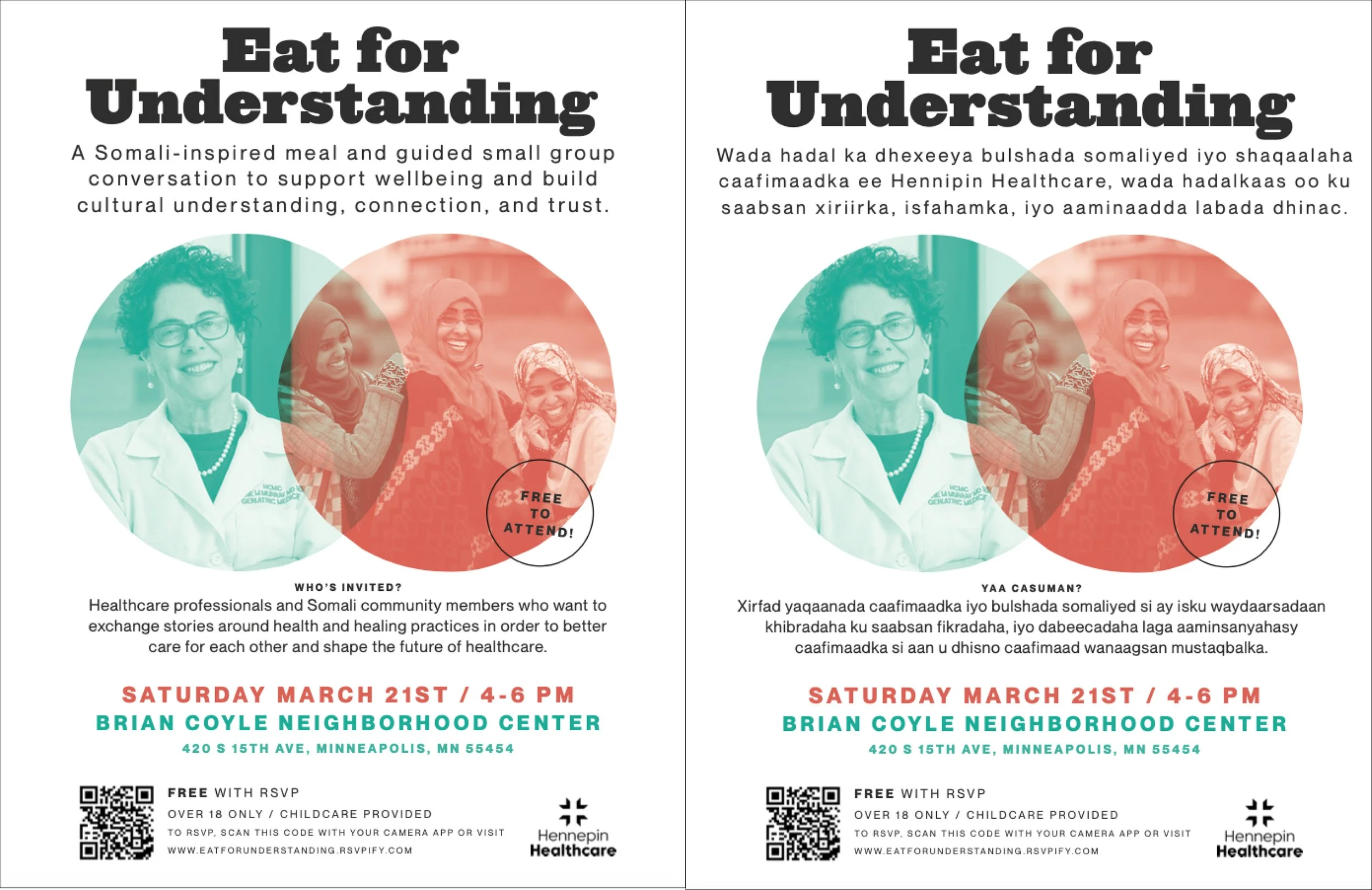

“Eat for Understanding” brings healthcare professionals and members of the Somali community together to enjoy a shared meal while discussing history, culture, feelings and experiences related to health, and create an opportunity to speak openly with each other about issues that impact our health and wellbeing

We believe that this event will lead to a deeper understanding between the healthcare community and the Somali community, less stigma around topics of health and wellbeing, new ideas on how to support each other and ourselves, and new ideas for supporting mental health in the Somali community.

Team: Jama Kheyre, Hanna Mumin, Fardowsa Omar, Andrea Brown

Role: Service Designer

Methods: Journey Mapping, Prototyping

Tools: Adobe InDesign, Google Forms

Deliverables: Service Blueprint, Prototype Findings Report

The Process

Understanding Community Needs and Perceptions

To start, we needed to ensure that we were grounded in the existing research to understand the wider cultural context. We conducted secondary research, conducting expert interviews with non-profit leaders, hospital translators and Somali religious leaders, to better scope the project and frame the opportunity space. We learned:

Traditional Somali culture is an oral culture, where news is spread via word of mouth

There is some suspicion and distrust of institutions and government as a result of civil unrest and previous “community engagement” partnerships

Religion plays an important role in health and healthcare - it is often the first step of getting support is through the Mosque

Mental health is a huge taboo and stigma is a huge barrier

Clinical mental health terms are not meaningful in Somali language - describe symptoms or common feelings and experiences instead

We brought this information, along with our “How Might We” question to a kickoff meeting with community leaders and brainstormed our project learning objectives and received feedback on potential methods to ensure we were honoring, not offending, the Somali culture. We also hired three passionate Community Engagement Leaders (CELs) to build and deepen equal collaboration between all critical stakeholders, especially those with lived experience.

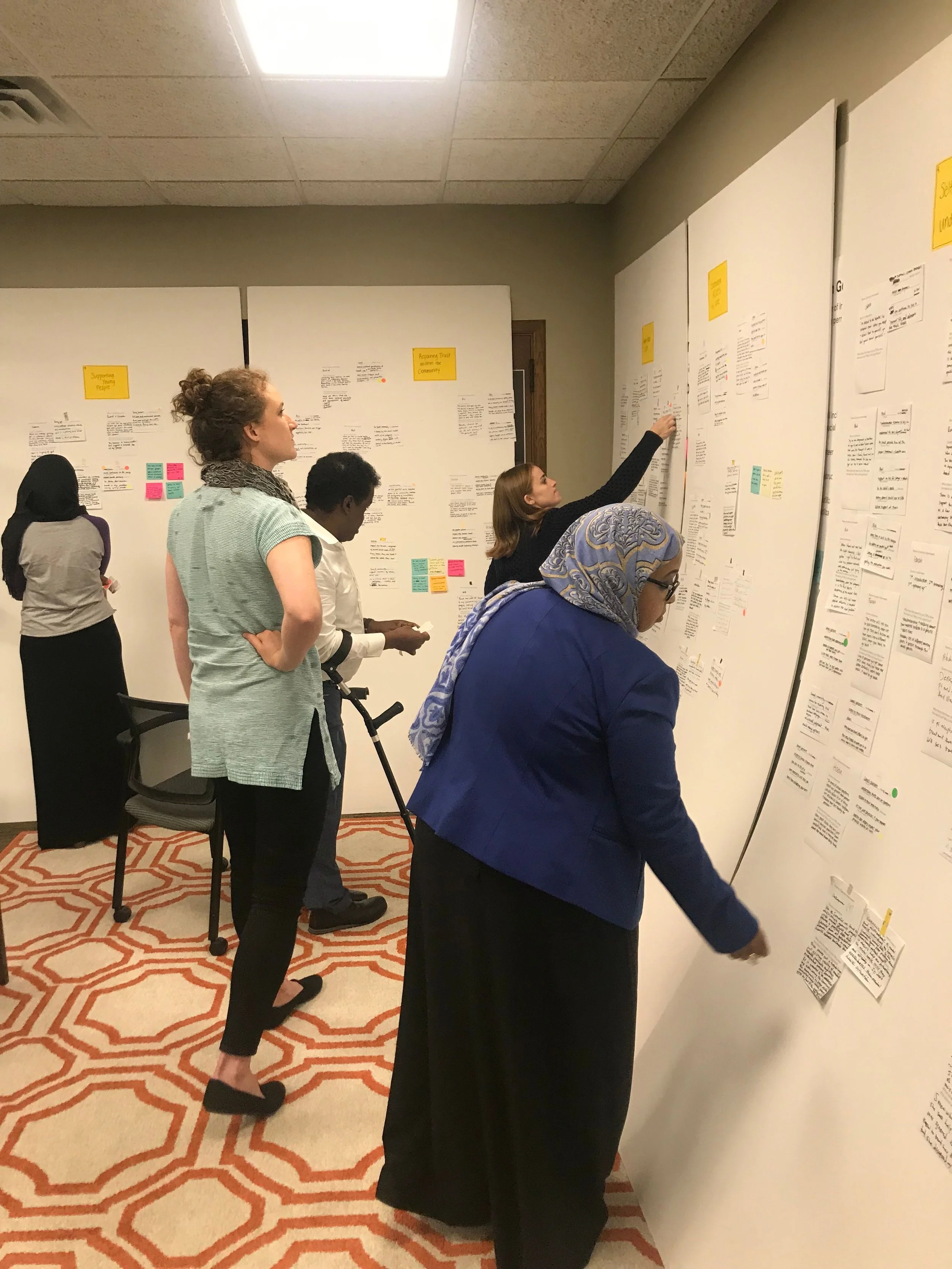

With our CELs in place, my design partner and I followed a weekly drum beat of prepping for a co-creation session, facilitating the session, and synthesizing what we heard to then reflect in the upcoming week’s session. It was important to us that we also build capability with our CELs, so each week, we also included skill-sharing in human-centered design principals and methods. As a team we conducted several rounds of research, ranging from 1:1 interviews, focus groups, fly-on-the-wall observations, and expert interviews. Our research goals were to understand what were the current perceptions of mental health and mental health support, what were the current experience with mental health services and barriers accessing those services, and what would be the idea way to support mental health in the future.

Over the course of two weeks, the team met with 40+ patients, spiritual leaders, social activists, care team members, and community health specialists and hosted two focus groups with patients who had previously received support from HHS’s mental health services.

Framing the Opportunities

To synthesize the learnings, each team member read through the transcripts, highlighted key quotes, and created Need Statements.

Through affinity diagramming, several insights emerged. First, that Fear and misunderstanding prevent conversations about mental health. We were starting to see patters that many people in the Somali community had a narrow and sometimes negative view of mental illness that discourages honest conversations about the many different ways that mental health needs can show up and be addressed.

“There are rumors that if you are here and you have a mental illness your children will be taken away from you, or you won’t get the things you need because you’ll be labeled as crazy.” - Somali Community Member

We also saw a theme emerge around lack of cultural awareness in the hospital staff, which limited empathy and broke patient trust. Lack of understanding into the unique history, needs and preferences of Somali patients left healthcare staff feeling ineffective and drained, and left patients feeling disrespected and unsure where to turn for trusted guidance.

“I don’t know the history of Somalia. The migration of people? The events? The experience? We need a better understanding of what they have experienced. That helps you communicate better with people.”

With these two opportunity areas in mind, our guiding HMW’s became: “How might we increase understanding of the wide range of mental health challenges that Somali people can face and the many ways of successfully managing them?” And “How might we increase staff understanding and empathy towards the Somali refugee and resettlement experience?”

Refining the Concepts

The team then ideated around these two questions to generate 40+ service concepts, which were then voted on using the dot method to prioritize four concepts.

To further refine and shape the concepts, we hosting a co-creation session with 25 members from local nonprofits, hospital staff, and community members. We utilized design scenarios and storyboarding, pulling many verbatim quotes directly from our research, to inspire each group to create a fully-formed concept. Each table then shared their output and participants were asked to rank the ideas based on impact and feasibility.

The community vote brought Staff Training and Empathy Building to the top, so we had discussions around what it meant to create a powerful learning experience. We concluded that an experience that allows for human connection, interaction, and a chance to learn new skills was essential. Given previous experience and cultural considerations, all of our ideas included a shared meal and intentional conversation, as this was believed to be the best way to build deep empathy and gain new perspectives. We again brought four concepts into a co-creation session, this time designing the service blueprint, utilizing storyboarding, card sorting activities and once again, community prioritization.

The output was used to create our prioritized prototype:

The event was designed to unfold in four acts:

1. Arriving & Getting Settled

Participants are greeted with a welcoming and engaging environment, including: Preprinted name tags with first names only to ensure equitable conversation, table assignments with a curated mix of community members & healthcare professionals, & table agreements to make sure the everyone feels heard & respected.

2. Setting the Stage for Shared Understanding

A video brings many stories and voices together to kick off the conversation. The video features community members and healthcare professionals speaking on the topic of “healthcare beliefs, attitudes and practices” and ends with the question “What is the ideal relationship between you and your healthcare provider?”

3. Learning from Each Other

Questions guide meaningful conversation and cultural exchange. Each course is paired with a question, and facilitators lead discussion and ensures everyone is heard and the table stays on topic. Participants respond to questions by sharing their personal experiences and perspectives.

4. Applying What We’ve Learned

The final course provides an opportunity to capture learnings and reflection. Dessert is served with the final question: “What will you take away from this discussion?” Participants can mingle and connect with people from other tables before leaving & everyone leaves feeling their time was well spent.

Making it Real

Over the course of the next month, the team went through every aspect of the event, from scouting an event location and cater to formalizing table agreements and securing a video that would set the stage. Each week, my design partner and I would create fodder for our core team to respond to, until we had the full service blueprint formalized.

And then Covid Happened…

With an in-person event on hold for an undetermined amount of time, the team quickly pivoted to create Tea-For-Understanding, a virtual small group conversation over tea designed to support well-being and build cultural understanding, connection and trust. While a shared meal was ideal, we thought that providing ingredients to make Somali tea and cookies sorced from a local social enterprise would work in a pinch. Given the updated venue, the service components changed slightly.

We hosted two virtual events, learning that people want a forum to gather and share stories, sharing as equals builds confidence and capacity to communicate across cultural differences & hearing from others de-stigmatizes mental health challenges. We also learned that there were barriers to connecting virtually, hearing specifically from the participants that virtual communication can be extremely disjointed and lack the warmth, spontaneity, and subtle non-verbal cues that help people get to know one another.

“Zoom is challenging - some of them its their first time. one of them said he tried to go on and couldn’t and abandoned it altogether. ”

We also learned several component findings, including that our personalized gestures (in the form of a welcome package) helped people feel cared for, that the curated content (in the form of a video) built the foundation of shared understanding, and that structured participation could benefit equitable conversation. The expectation that people would share at their own pace combined with the varied channels through which participants joined resulted in long pauses between responses and a need for the facilitator to intervene. We decided that more work was needed to support smooth and equitable sharing.

Given the pandemic and what we had learned through the virtual prototypes, my design partner and I created three paths forward and brought them to the team and our stakeholders. It was decided that because the virtual space wasn’t as equitable as we were hoping to create, the team made the decision to pause the project until we could host a smaller, in-person event.

The Findings and Recommendations

Providing human connection in a time when it’s needed most

After a three month pause, we were finally able to test out the in-person experience. Held on Boom Island, 10 guests, two Somali Facilitators, myself and my design partner hosted a new model of staff training and empathy building.

Several things were learned and the detailed findings can be reviewed in the Prototype Findings + Recommendations Report, but at a high level, we learned through post-event survey data and follow-up interviews that Eat For Understanding created an impactful combination for trust, knowledge and relationship-building between healthcare professionals and Somali community members, where all 10 participants stated they would want to attend similar events on a quarterly basis.

“We’re de-stigmatizing mental health because we’re all going through the same things in life in some shape or form. It opened up a lot for me in de-stigmatizing and breaking stereotypes around these issues.”

“It’s asking us as healthcare providers to be vulnerable too. Patient panels are interesting, and it does recognize that we aren’t doing a great job and have more growth in those areas, but it’s asking a group of people who have historically been marginalized to share their stories of enduring harm in our healthcare system. It’s recognizing that we need to change, but are not participating fully. There’s only so much that you can get from hearing the same thing over and over on those panels. By being asked to participate as ourselves and be engaged in an event like this, it was way more impactful.”

The Next Steps

The team synthesized the event feedback and came up with the ideal Eat for Understanding Experience:

Given the intensity of the pandemic at the time, resources were significantly constrained and the prototype was put on hold. We provided four paths forward when budget and time constraints weren’t as severe, including expanding the offering to other communities in the Twin Cities.